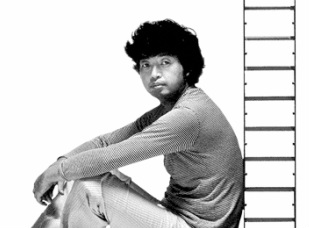

| Kuramata's designs reflect the confidence and creativity of postwar japan, retaining a strong identity based on traditional japanese aesthetics while breaking new ground through the use of innovative materials. he combined the Japanese concept of the unity of the arts with his fascination with contemporary western culture, inventing a new design vocabulary: : the ephemeral, the sensation of floating and release from gravity, transparency and the construction of light. Kuramata reassessed the relationship between form and function, imposing his own vision of the surreal and of minimalist ideals on everyday objects. Born 1934 in Tokyo between the wars, the son of an administrator who became vice-director of a scientific institute, Kuramata was raised in Japan. He received a traditional training in the woodcraft department at Tokyo's Polytechnic High School, and then went on to work in a furniture factory, the 'teikoku kizai company' (1953). he pursued his studies in interior design at the 'Kuwasawa Design School' in Tokyo (1956) -institute that taught western concepts of interior design- the he was hired by the small department store 'San-ai' as a designer of showcases as well as floor and window displays (1957). after a brief stint as a freelance designer for the retail giant 'Matsuya department store' (1964) the following year he opened his own design office in Tokyo (1965). During the 1970s and 80s, Kuramata, alert to the revolutionary possibilities of new technologies and industrial materials, seized upon acrylic, glass, aluminum, and steel mesh to create objects that appear to break free of gravity into airy realms of transparency and lightness. http://www.designboom.com/portrait/kuramata.html |

|

0 Comments

Walker has made his way to this remote corner of the globe from his native Britain in order, in that most clichéd of fashions, to find himself, to be ‘at one’ with the world. And yet, as he begins to experience the reality of his vision of unbound nature, he cannot help but collapse what he sees back again onto a familiar pictorial plane, constrained by language and proportion. The compulsion to command and compartmentalise nature appears overpowering, cementing man’s place at the centre of the world, imposing order like one of those “frock coats” so despised by Bataille (who instead envisioned an essentially formless universe).

The great American landscape has long resonated in popular culture as a site of ultimate romantic escapism, from the seductive wilderness of Marlboro Country advertisements, to countless film and television productions. Walker himself cites ‘couple on the run’ movies such as Badlands, Bonnie & Clyde, Gun Crazy and Natural Born Killers, where “the theme seems to be that in order for the couples to be together they are forced to transgress, often committing successive crimes and escaping civilization for the limitless bounds of the American landscape. It is only here that their love can exist.” But in Walker’s works we find no violence, no romanticised form of Bataillean transgression that might act as an ultimate gateway to the Real. The subject of Walker’s love is instead the landscape itself, his works centring on an intense, solitudinous relationship with nature. He engages in the pathetic fallacy, anthropomorphising the land as an entity capable of reciprocating his desires. And yet the landscape remains impassive; a love destined to be perpetually unrequited. Link to full article: http://www.metamodernism.com/2013/03/13/in-pursuit-of-elusive-horizons/

Both born in 1908 in Vienna. Otto Natzler pursued violin studies, attended a school for textile design, and worked as a textile designer. He met Gertrud Amon in 1933; she had attended commercial school and was working as a secretary while taking art instruction. Gertrud almost immediately interested Otto in clay. Primarily self-taught, they studied at the ceramic workshop of Franz Iskra for less than a year, then opened their first workshop in 1935. Almost from the start, their collaboration involved a division of labor, with Gertrud’s remarkable throwing and Otto’s mastery of glazes. They quickly found success, winning a silver medal at the 1937 World Exposition in Paris. In 1938 they married and emigrated from Austria to the United States, settling in Los Angeles, and soon acquired an international reputation. More exhibitions and awards followed, including retrospectives at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the American Craft Museum (now the Museum of Arts and Design), New York. By Gertrud’s death in 1971, they had created 25,000 works and Otto had developed 2,500 glazes. In the mid-1970s, Otto returned to work in clay, concentrating on slab construction. He went on to have numerous solo exhibitions and was named an American Craft Council Fellow in 1990. The Natzlers received the American Craft Council’s Gold Medal in 2001. Otto Natzler died in 2007.

http://craftcouncil.org/artist/otto-natzler-gertrud-natzler Examined Life pulls philosophy out of academic journals and classrooms, and puts it back on the streets. In Examined Life, filmmaker Astra Taylor accompanies some of today's most influential thinkers on a series of unique excursions through places and spaces that hold particular resonance for them and their ideas. Peter Singer's thoughts on the ethics of consumption are amplified against the backdrop of Fifth Avenue's posh boutiques. Michael Hardt ponders the nature of revolution while surrounded by symbols of wealth and leisure. Judith Butler and a friend stroll through San Francisco's Mission District questioning our culture's fixation on individualism. And while driving through Manhattan, Cornel West - perhaps America's best-known public intellectual - compares philosophy to jazz and blues, reminding us how intense and invigorating a life of the mind can be. Offering privileged moments with great thinkers from fields ranging from moral philosophy to cultural theory, Examined Life reveals philosophy's power to transform the way we see the world around us and imagine our place in it. - imbd.com |